Sometimes something unexpected happens.

In the middle of November 2022 I was contacted by one of John´s relatives, Bill Dunbar. He wrote:

”Hello, Ms. Garde!

I am one of John’s nephews. He was a father figure to my sisters and me… and all of my cousins! No uncle was ever loved more than Uncle Johnny. He was SO silly… and caring and loving and affectionate and generous and honest. We all miss him terribly and talk about him constantly — even 34 years after he died. His absence is particularly difficult for my mother who could not have been closer to him. They were six years apart and she describes how throughout childhood and into adulthood Johnny would take her hand whenever they walked together… even in a grocery store. I’ve attached a photo from 1965 … you’ll note they’re holding hands!

Uncle Johnny helped so many young men with AIDS whose families had abandoned them, and he introduced them to ours. It was a tragic but very important time in our lives, particularly since my dad had died suddenly and mom moved in with Johnny. They did everything together… until AIDS struck.

Uncle John touched so many people throughout his life, so it’s no surprise that he made an impression on you. We’re grateful you spent time with him… he was a character!!

I know my mom, my sisters, my cousins, and I would love to see your interview with him… is it available somewhere?

Thank you for your time. Please let me know if there’s anything I can do for you.

I try to do my work in a chronological order, from when I came to San Francisco in August 1987, but decided to write about John now, because his family contacted me. But it took a while, because I suddenly got pneumonia. Meanwhile we made friends on Facebook.

Suddenly Bill wrote on FB that his mother, Josephine ” Jo”, Dunbar Snow, had passed away, at 96 years old.

When I came to San Francisco in August of 1987, HIV/AIDS had been going on for years, and I met John LoCoco at a workshop for hospital staff and volunteers, ”Care for Caregivers”, where I was allowed to be an observer. It was lead by Drama therapist Raymond Jacobs from New York.

It was a moving and interesting workshop, mostly about grief.

Some caregivers were stuck in grief, and could not cry – they had seen so many patients and friends die. Some of the participants were HIV-positive them selves, and could clearly see what was to come. Some knew so many in the AIDS Ward they were working in, that they did not know which room to go to first.

I was allowed to take part in some of the exercises, and it was during one of them that I noticed John.

We were sitting in a circle and we were asked to talk about our shoes; what they said about us. I don´t remember what I said, but I remember what John said; he did not know if he would walk in them so much longer, as he was sick.

We also talked about ”five years ahead”, and John said he didn´t know if he would be around in five years. During one of the breaks I asked if we could talk, and he said yes.

John was going to meet Pope John Paul II, the very next day, as the Pope was visiting San Francisco. John had been invited to meet the Pop together with a number of people, and he was invited as a Catholic person with AIDS.

We met a week later at the Pacific Presbyterian Medical Center where John had been a patient, and where he was now active as a volunteer. He showed me around the hospital, and took me to the Planetree unit, where he had been treated, and then we sat down in a small room to talk.

When I met John he had survived 3 bouts of Pneumocystis, Tuberculosis and Kaposi´s sarcoma in the lymph nodes. (John did not mention which pneumonia he had had.)

One of the episodes with Pneumocystis was specifically serious, it happened in March 1987.

- I was at the hospital for almost 6 weeks and I was not supposed to pull through. My family came and said goodbye. I was down to maybe two or three days to live, and something in my system was shutting down. And then something happened.

John had showed me the room he had been in at the Planetree unit.

- This Planetree is quite unusual. It´s holistic, and they believe in vitamins and hugging, and you know, with all that care they pulled me through.

John thought that if he pulled through this time, he was going to do more for others, so he got involved in the volunteer program and went through the training.

- So, that´s what I´m doing. I´m volunteering working with patients that are newly diagnosed.

When John showed me around the unit, he handed out a paper to the patients. It was a restaurant that offered free gourmet lunches to the patients; sandwiches, hamburgers, pasta. And Chocolate Mousse.

- What you saw this morning was primarily getting the meal thing out, but then we go back again, and we sit down, if they want to sit and chat – see what we can do in regards to family, or… anything they need, letter writing or wills, or, anything that they need… It´s very rewarding.

John also did similar work with Most Holy Redeemer, the Catholic parish he associated with in San Francisco, that had an outreach program for People with AIDS at home, with emotional and physical support.

- And… We have drop-in-sessions for parents who need help. I find that the most… rewarding. Not only working with the patients, but when they are lucky enough to have a parent that´s interested in them, in their well being, working with that parent… We have quite a few of the young people here, their parents reject them, they don´t want to be part of their suffering, and it´s embarrassing to them, and so… They just leave the child or they ship them to San Francisco, and they want no part of it, and that´s not uncommon. We are lucky in San Francisco to be the prototype.

John had worked with the media during the last two weeks, because of his upcoming meeting with the Pope, and he found that people were very impressed with the work that was going on in San Francisco, and people came to San Francisco from other places in the US to get help.

- We have people from New York. I visited two last week who came from New York to San Francisco for their care and their support, cause they felt it was more sensitive here… So we´re lucky. I´m very proud of the city

John had worked in real estate, and before that he was a counselor for about 12 years.

- I counseled young people with emotional problems, young married couples, people who were heavy in (to) narcotics, their families. I worked through the Arch Dioceses in Orange County, which is between Los Angeles and San Diego.

John had never had any problems with him being gay in the Catholic church. The Arch bishop, later Cardinal Timothy Manning, knew his partner, and it wasn´t a problem. He had appointed John as one of the first lay people to distribute communion, about 15 years ago.

- You know working with young people, some were gay, others were´nt, and that wasn´t important. The main thing was what we did for the young people, so I´ve never had any difficulty. I never worded out I´m gay, and I´m working with young teenagers, or whatever, I never entered in to that picture.

- They didn´t bother you about it, anyway?

- No, very supportive. And the interesting thing now that they know that I have AIDS… and I´m back in San Francisco, the communications have just been wonderful.

Some of the young people that were 16 and 18 when he met them were now in their thirties, and would come to visit, and Cardinal Manning had written to John a couple of times.

John had had a partner for 22 years, but that changed when he suddenly came down with AIDS. He had thought the relationship was monogamous, but…

- I really fought the fact that I had it, cause there was no way I could have gotten AIDS, cause I was only with one individual for that many years, and my blood test had come out negative, not positive. Then they said I had pneumocystis, and I still couldn´t understand it.

Four months into his diagnosis he had reason to look into his partners dresser to get something, and there he found a ID card for Club Baths, a chain of gay bathhouses in the US and Canada. He confronted his partner about it.

- And he, through business he had to go out of town a lot, and he said it was just when he was out of town, and it was no big deal. Well to me it was, because… I ended up with AIDS, and found out he was a carrier. He has AIDS now himself, but he was a carrier

They broke up for a year and a half, because John was very bitter.

- When I was dying… I was still very bitter regarding him, and when I got well, this girl I know said that God didn´t want me, because I was dying with this hatred, and that was foreign to my system.

Here John joked about it – a friend of his had said: ”Don´t change! Keep on hating him, cause then God won´t take you!” John laughed.

- But after I got out of the hospital, and all the Planetree nurses talked to me about it, you know the once you met today (here he mentioned two, Carol and Becky) you know, if God is forgiving, why should I not be… more understanding,

John rented a little cabin and went and did his own retreat for about a week, analysing the whole thing, and when he came back he called his partner and he moved back in.

- And is it ok now?

- I still have a little… I don´t talk to him about it, but I still have a little… 10 %… you know a little resentment, but he´s having a difficult time… His AIDS has affected the back of his brain, so he.. will become incoherent, he´ll need custodial care, pretty soon.

- Does he have dementia?

- A little bit, yeah. He has different days, some days are really good, and then – it´s affected his lower extremities, sometimes he can´t walk too well, but he´s …

We agreed on that it was good that they could be together, considering that they knew each other so well.

- So how was it to start working with other patients?

- Sometimes… it´s very rewarding, sometimes it´s very rough – you know you get attached to some of the young people here.

One who was really young, 25, was Eric… He had KS and quite a few lesions on his face, and it´s gotten to his eyes. And when you´d first go in, he would sort of turn the other way, not to look at you. We became very good friends, and from then on when I´d go in to his room, he´d just brighten up in a big big smile.

He had checked out of the hospital to go home, and I saw him at Short-stay on Friday when I was having a transfusion, and the following Monday he is dead. And… it really gets to you. And there´s maybe four or five in the last… month, that we´ve lost… that´s hard. It´s not that you´re just going through it your self, but it´s going to happen to you too, it´s just that…

John compared it to a battlefield, to be fighting a war, and you´d hear about people dying, and that the man next to you, on the left or right hand died, and that it was going on, constantly.

- It´s nothing else but a war, and this particular enemy doesn´t take any prisoners, you know, so you have to fight, you have to keep your weapons… ready to fight. And that´s what we do here, is trying to… give that … support to people, not to give up, cause people can die from a cold if you just give in to it, but they need constant support.

When you greet the patients, they are very receptive, they are very reaching out to you, more so than if you were an orderly or an intern or even a nurse, because you are going through it with them and they can relate to you when you are there, running around the hospital and they see you there, and that gives them a good… feeling, you know. If this guy went through it, and here he is trying to help us – so that´s a good feeling. There has to be more volunteers, within our own ranks.

I asked John about the five years we had been talking about at Care for Caregivers. He had said he didn´t know if he would be around.

- Do you plan for not being around, I mean how do you…

- I don´t really feel I´ll be here five years from now, unless something… really a miracle happens… I really do live from day to day, and you know people can say they do, but I really do. I catch my self from planning things six months from now, like I used to. I was the kind that would sit down and write things out for the next eighteen months, I don´t do that, no…

John had two nieces that had been pregnant, and around Christmas he had thought to him self that he hoped he would be there ” I wish I´m here when the babies are born”, and he was, they were both born.

- I don´t know… and I´m not being dramatic, is that none of us know when you go in to a war zone what´s gonna happen. I… I thought… You know they said you are going to last between six and eighteen months. Well, I´ve passed my eighteenth month… I don´t know, I really don´t know. I hope like the rest of us we´ll be here for a long time, but I don´t see how. I´m sort of wearing down, you know, my self, physically. I have like more night sweats, I have to go for a MRI, which is a brain scan.

Many things had happened to John and he had often thought ”Well, this is it!”, and then it wasn´t.

- So my luggage has been packed a few times, but the porter didn´t show up, you know, so… I feel that each week, by the end of the week if I know that I was able to touch somebody´s life… if I can do that each week…

Those parents, you know, that we met today… (it was a couple who talked to John briefly) who are just… reaching out, without saying it, but just saying: ”Help me, help me, I knew my son was gay, but I didn´t even know he was sick!” And here is this kid that´s had ARC for… it looks like he has full blown AIDS now, and if you can just… They might not know who you are, you know six month´s from now, but at the time, when they are so… vulnerable and they need help, if you can just touch them, I think it´s worth it. And that´s why I´m here a lot…

I have a loveaffair with half of the nurses around here, because I know what they give. They are such an intricate part of a patient´s pulling through, you know, not treating them like cattle. The nurses here are outstanding.

We talked about the worry that AIDS would be turned into big business, and here he mentioned SHANTI as an example, (where there had been problems), and as I write that I remember that there were demonstrations about this – but I don´t remember what year – ”Take back AIDS” from the people that used AIDS to make money, and careers.

We also talked about compassion, that it must be constant, even though there were now so many that were sick.

- Yeah, there is… two years ago… when I almost, when I was diagnosed, it was: ”OH! He has AIDS!” And now we have to watch when there have been thousands of others, when you hear of a new person getting AIDS, on September 24, 1987, you get ”Oh, there´s another one! That´s too bad… ” You have to show the same compassion.

John talked about the thrill when a child is born.

- You never get tired of new babies coming on earth… that same compassion has to be there when a person is diagnosed and he´s dying, or that he has AIDS or whatever… Sometimes we come here like today, Thank God there were´nt many, but two weeks ago there were 18 patients, and two or three volunteers. We all said, ”Well there´s 18, so we´re gonna work a little harder, everyone needs our attention”, you know… It´s just… it has to be consistent and constant, because any person going through this, it´s a shock when you find out, you know, here in the US or in Sweden or in Italy or where ever, it´s a shock, and that person needs a lot of understanding.

I wondered about John´s family.

- My father passed away, my mom is alive, and she´s quite elderly, but I have my brother´s and sister´s who I´m very close to, and they are going along with all this with me. And my nieces and nephews, who are in their late twenties or early thirties now… are so much a part of my life, every single one of them, from Seattle down to Southern California.

When I was ill last, they were all here. They were hugging and saying ” You are not going, uncle John, don’t go, we need you! ”

And they follow up, and even with their children now… I have become like their patriarch, and they are very understanding about all this, and very supportive and very loving. So I´m lucky…

So I hear of kids that don´t have that, I really have empathy for them, you know, I really… You know when your loved ones turn you down… So that´s why I´m given so much love, that I have to get rid of it, cause I don´t have room for more. So, I´m giving it to the strangers… and that´s been very rewarding.

We had come to the Pope, John Paul II. John had been asked to see him by one of the priests in Most Holy Redeemer church, Father/Reverend McGuire.

- I didn´t want to do it, cause I don´t really politically go along with what´s coming out of the Pope, out of Rome. And… my pastor said: ”You know John… you might help ONE person with all this, because of the exposure. And I thought about it, and I did it, and… It came to pass right away. I was interviewed at CNN., which is a cable national network, you know it´s a quite a lengthy interview, and about four days later they called and asked if I would accept a call from a lady in New York, and I said yes.

She called to let me know her son was dying of AIDS in a hospital in New York, and he had refused to see a priest, and then he saw my little segment and told his mother to call a priest. And then, a week later she called to say that he had died, and the day before he died he told her to get back to me, to let me know that the church had embraced him, so that was worth it… You know, that was worth it.

John said he was extremely thrilled, knowing that he represented gay men and women throughout the world.

- And then also those of us who have AIDS. So that was the pride, the thrill…

John gave 33 interviews during this time, also together with others.

- So I thought we were able to express ourselves… People realise that there are different facets of heterosexual life… There are extreme people, there are quiet people, there are working people, politicians, whatever, you know married people, and all different how they lead their lives, different type.

But the average person thinks of homosexuality as one lump, we don´t have different facets, we are all extreme homosexuals.

So what this did was to allow us to show the public that we are… your doctors and your nurses, and your teachers and nuns and your missionaries, and your politicians and judges and your grocery clerk, and whatever, AND by the way, they happen to be gay.

They know that in San Francisco, and they know that in New York, but they don´t know that in Idaho or Georgia. And all this Pope-attention allowed it.

John had certain things he wanted to tell the Pope, about things he had learned in school, as he grew up in San Francisco.

- I was not taught to fear Christ, I was taught to love Christ and to follow him, because he fed the hungry, he took care of the sick, he clothed the naked, his best friends were prostitutes, he embraced the lepers, and he attended the dying – and that´s being Christlike.

So when I was able to talk to the Pope, I told him that I prayed that he would be more Christlike… and he lifted his hand and touched my cheek, that he would pray for me too.

There were things that John was disappointed with, for example that the Pope´s speeches were written back in Rome, before he came to San Francisco.

- But I feel that he had to see… what love and compassion is here, and then when he gets back home, he´ll have to register and digest some of it, and I think he will. It´s done an awful lot of good for the church within the United States, because of what we were able to show him.

- You said it was very moving.

- Mm, it really was… He has a lot of charisma, he really does… He reminds me of a stirring parent, well, like my father was from the old country, Italy. My mother and father are from Italy, from Sicily, and they had rules: This was it! He had all the love, he would kiss me every night and tuck me in bed, even when I was 20 years old – still tuck me in bed.

But he had his rules, so there could be some things that I knew he wouldn´t like, so I wouldn´t tell him, and I´d use my own thought.

John lead his own life, without letting his father know that he was breaking the rules, his father´s rules.

- Well, the Pope is that way. He has some of his old world rules, but he hasn´t caught up with 1987, you know with birth control and women´s rights, and women being a part of the clergy, you now, he hasn´t caught up with that yet, so… I found him to be rigid, but compassionate, you know.

John talked about that the Pope came from Poland, and that he was very conservative, and he then referred to a previous Pope.

- I think if we had a Pope John XXIII now, things would be different, there´d be more compassion and more… love coming out.

When the Pope was in the church, and had met the AIDS-patients, among them a five year old boy that he held, they wanted him to go to Coming Home Hospice, and the Pope wanted to go, but the police and the security said no.

I wondered what John would say to people who were working with AIDS.

- You have a lot of love and compassion… to be doing that kind of work… and you might get burnt out, so you´d get away from it when you have to, recharge your batteries and go back.

But if you have the ability to embrace and to love more people, it´s such a rewarding… and giving life, cause that´s what you are doing – you are constantly embracing those who are suffering. It´s almost as if you were – you don´t have to be super religious, but if you were… a nun, or a monk or a brother or something, that you are dedicating your self to this.

It´s not normal, it´s not a normal life, you know, you walk away from it, but it´s still on your mind when you go home and go to bed, wondering about that person.

John wanted to put all the people he knew who were helping people with AIDS, in to a xerox machine, so they could get more and more of them. Not only young people, but older men and women.

- I met five or six mothers who´ve lost their sons with AIDS, and they´re out volunteering, helping others, and even if… it´s not a mother who lost a child, I think there´s a great need for older women to volunteer, to be that mother image for these kids, to hug them and embrace them. I just think it… you know, it can´t just be young people or super sharp guys or whatever, it´s gotta be all kind. But when you see an older man and an older woman volunteering, who are heterosexual, that really grabs me, I just think that´s marvelous. You know they… bake cakes and write letters and hug, you know all that good, but… you know it´s rough.

John talked about reactions from partners who are not involved and who don´t understand that you give so much attention to strangers, and not to them.

- So I think there´s a lot of hardships that are involved. We need, more seminars, we need getting together, we need more conferences to share… But if you are a volunteer and it becomes routine… then you should get out of it.

We had come to the end of the interview, and I wondered about Unfinished business. Had he taken care of things? And John had, indeed! Everything was arranged.

- I took care of that sort of in the beginning, so I wouldn´t have to worry about it anymore.

John had already paid for his funeral arrangements.

- What are you going to do? Will you be cremated?

- I´m having a Memorial mass at Most Holy Redeemer, and … I have the program already done… I had it printed. My niece has it.

- Where will your ashes go?

- San Francisco Bay, near the Golden Gate Bridge.

John said he had a whole bunch of nieces, but it was one of them who was going to spread his ashes. He said she was very loving, unpretentious, always there, he didn´t give me her name, but she was his buddy.

John was going on a visit. He had a nephew who had named a child after him, so there was now a new John LoCoco, three weeks old.

- And that´s quite a thrill.

I said to John that he was blessed, and he agreed.

I wondered if there was anything else he wanted to say, and he said that it was wonderful that I was there, absorbing all of this.

- Love and emotion… and knowing that we´re trying to share it with you, and then you´re gonna bring that back home to your people. I think that´s very rewarding.

Before I left for Sweden, I found out that John was ill and back in the hospital, so I went for a short visit, and right then his partner Don was there, and we said hello.

I wrote to John, but I did not hear from him. Eventually I called him, on June 21st, 1988, and found out that his letter to me had been returned.

I have been stalked by a mentally sick person, and I had told the post office that my address was not to be revealed, should anyone ask. That message was understood to mean that no mail was to be delivered to my address, and it was through John I found that out.

When I spoke to John he sounded very sad. He had had his sixth pneumonia.

- I don´t know why God wants me to go through this.

John did not live with his partner any longer.

John said that he was taken care of by Most Holy Redeemer and by his loving family; nieces and nephews, that would come to him.

- You are a loving friend to call. God bless you.

Those were actually the last words spoken to me by John.

I never knew the full name of John´s partner, until now through Bill, and I found his obituary among the Bay Area Reporter´s obituaries. He passed away August 8th, 1988.

I returned to San Francisco in October 1988, and immediately started to contact people.

I follow my notes here, from October 17th, that turned out to be a very important and dramatic day.

There is a short note: ”John LoCoco, where are you? No one knows. ”

”I looked for John LoCoco in vain, and found out through Most Holy Redeemer that he was back in the hospital, and that they did not think he would make it this time. ”

I was staying with Jan Baer again, in Bernal Heights, and did not know how to make it really fast down to town, finding a bus, trying to explain where I wanted to go, it was hopeless – so I stopped a car, explained the situation and asked the driver, who happened to be a neighbour, if he would take me to the hospital, and he said yes. I was so upset, that he told me I had to calm down if I wanted him to take me there. I did, and he actually drove me to entrance of the Presbytarian, and I thanked him so much!

”I cried in the elevator, scared I had come too late, and I almost ran passed the rooms, but I couldn´t find John. However when I asked about him, I was shown in to one of the rooms I had passed by, and I did not recognize him. He was half his size, on oxygen, and he looked totally different.

His family was there, nieces and nephews, talking to uncle John that he has meant everything to them. They said that he has been like a father to them, more than anyone else, that he has been so helpful to everyone, and traveled to them if there had been problems; he has always been there for the family. ”

The family left the room for a while, but he had a sister there, and it took me some time to realise that she was not his sister, but a nun, Sister Cleta Herold dressed in private clothes. It was Sister Cleta that made John aware of that I was there. He was lying on his left side, and I sat in front of him. His eyes were almost closed.

”She said that he such a strong heart that does not want to give up. She told me that he has ordered his Memorial service to be on Saturday, and has arranged everything, as if he knows he´ll be dead by then.

John had a volunteer. ( Or maybe he was one of the volunteers at the hospital who took care of many patients, like John had done.) He seemed to be in a hurry and said to me that John had been given a lot of Morphine and Valium, but that he hears what one says, so I could talk to him. Then he leaned over and talked to John and said that he was going for lunch, and then he said: ”Let go, just let go… Go to the Light John! Go to the Light!”, and vanished.

I talked to John, I said I was glad to be there, and I gave him a picture of the Madonna that I use to carry around in my wallet, that sister Cleta put up on the wall. She said: ”Pia has brought a picture of our Blessed Mother”. She wanted to raise up his bed, and she said: ”You are flying now, right into the arms of Jesus, that´s what you are doing now John, you are flying right into the arms of Jesus.”

I had an interview to do, so I had to leave. I ate something downstairs and then went up to John´s room again to say goodbye. We were alone in the room then.

I held his hand, and leaned on the side to look in to his eyes, but I could only see one, as he was laying on the side. He seemed to look straight at me, and he looked very sad.

I patted him and did not know what to say. I did not want to repeat the words ”Go to the Light!”, so I said ” If we don´t see each other again here, we´ll see each other Saturday. ”

I was told that John just wanted to die now, he had done all he could. He did not want any life-sustaining treatment, he just really wanted to die. All he got was some water.

I made the interview with one of the volunteers from SHANTI, and went home to Jan Baer, who I was staying with. I was very very nervous, and did not understand why.

”I called the hospital to ask how John was doing, and the woman who answered sounded really surprised at my question, and after a few moments of silence, she said that John had died five minutes ago. Then she said: ´Less then that, three minutes ago. It just happened.´

The family had been with him, so I asked her to send them a greeting. Maybe someone could call me?”

”Amy, one of John´s nieces called. She said John´s death had been easy, he just stopped breathing. He did not have to gasp for breath or anything like that, he just stopped breathing. And they were all there with him. ”

She invited me to the Memorial Mass at Most Holy Redeemer.

I was just stunned, that it had all happened in a few hours.

Had I not called Most Holy Redeemer…

The Memorial Mass took place the following Saturday, and it was very moving. Many of John´s relatives took part, among them Bill Dunbar, who contacted me recently.

The Celebrant was Rev. Anthony McGuire, and I think he was the man who talked first about John. ( I recorded the service, but did not comment.)

He had been new to the congregation, and he had had a sense of darkness coming over the Parish – he did not specify what it was all about, maybe it had to do with HIV/AIDS – but he did not know what to do.

One day he saw a note on the board about an event with Gay Italian Alliance. There were all sorts of Catholic groups, but what was this?! He decided to go there, and he was nervous, stepping in to the dark, he thought.

”And who met me at the door, but John. Big apron on, and he welcomed me and thanked me for coming, and he introduced me to everyone there. He showed me what was going on in the pots and pans, and he told me how happy he was that I was there, and how happy he was to be (hard to hear) Founder of the Gay Italian Alliance and a member of the Roman Catholic Church.

When I left that evening I felt like light had come in to my life, and I felt that I had been given a much clearer direction, as how to deal with the people in my Parish – was the way that John had dealt with me. With great respect, great friendliness, great hospitality and… with an insistence that as a gay man he was also Italian, also Catholic and proud of all of those. ´There was a man sent from God, whose name was John. He came as a witness, to bear witness about the light, that all might believe through him´.”

He continued to tell stories about John, and one of them was how he had held two banquets at a hotel, one for family and friends, and one for the staff at the Planetree unit at the Presbyterian Hospital, for doctors, nurses, hospital workers, ”who were astoundly wonderful to him”. ”

”A beautiful example of a person celebrating life, as life, as physical life diminished, the life of the spirit expanded and grew and drew us all in to the celebration.”

After the Memorial Mass, John invited us all to a pasta brunch, arranged by GIA, Gay Italian Alliance. A joyous occasion.

My contact with John LoCoco became very personal, and I could feel his ”presence”, especially in church, for a long time, and especially around Christmas, when one could hear the words: ”There was a man sent from God, whose name was John. He came as a witness, to bear witness about the light, that all might believe through him.”

For a long time I wondered where John was buried, until a suddenly remembered he had said he wanted his ashes to be in the Bay, near Golden Gate Bridge, so when I returned to San Francisco in 2014, I threw white roses in to the water, not far away from the bridge.

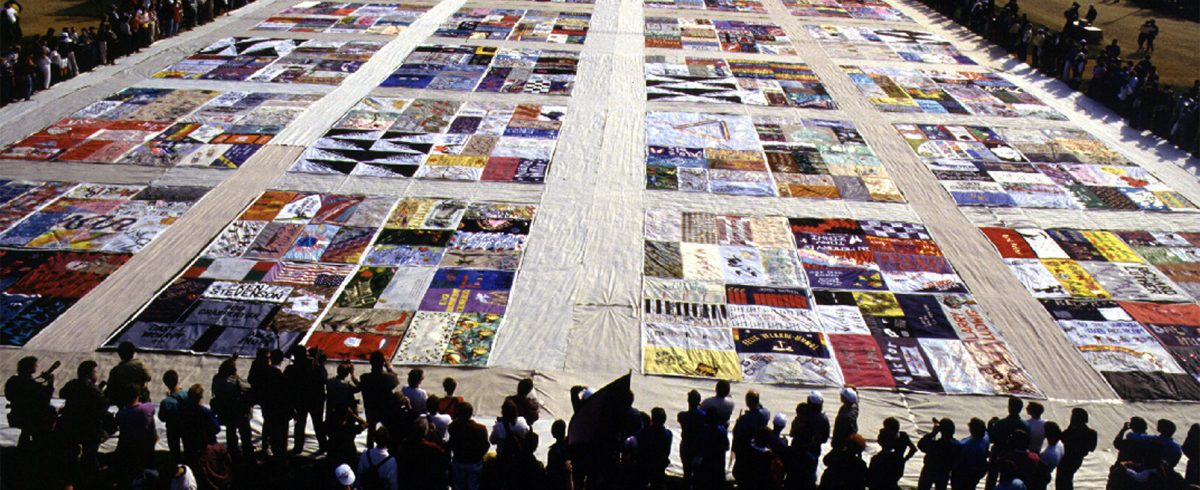

Here is John´s Panel in the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, where you also see the photo of John and Pope John Paul II.

I also became friends with Sister Cleta Herold, and followed her as far as I could. She was the one who sent me the photo of John and the Pope.

Sister Cleta stayed in an apartment at Most Holy Redeemer, as she had been a Pastor Associate there, much involved in the AIDS epidemic. I visited her there many years later. She gave me this photo.

She was becoming forgetful, she said, and was planning her funeral. She belonged to Sisters of the Presentation, and she eventually moved back to the Motherhouse in San Francisco, and I visited her there in 2014, when she was quite forgetful.

Sister Cleta Herold PBVM (religious name Sister Mary Cletus) passed away on September 26, 2016.

As John´s Memorial Mass took place in his church, Most Holy Redeemer Catholic church, I ordered a tile in memory of John and everyone I had met that had died of AIDS, at the Commemorative Wall and Fountain in the Church Garden.

It was dedicated to former pastor Fr. Tony McGuire, Sr. Cleta Herold, and in memory of former pastor Fr. Zachery Shore, on April 29, 2013. Sister Cleta was there at the time, as well as Fr. Tony McGuire and others; parishioners and neighbors.